To Truly Remember the Fallen, We Must Still Resist Fascism

At 11AM, Sunday 9/11/2025, the UK will remember veterans who lost their lives during WW1 & WW2. This article poses as a much needed reminder of what was fought against!

Remembrance Sunday provides us with an opportunity to show our gratitude to all members of the British and commonwealth forces who served, and lost their lives, across the two world wars. It also compels us to think about what regimes the allies fought against, and offers a pause of reflection for those who understand that history is prone to repeating itself, although many are blinded by their own lack of self-awareness while living out the scenario in reality.

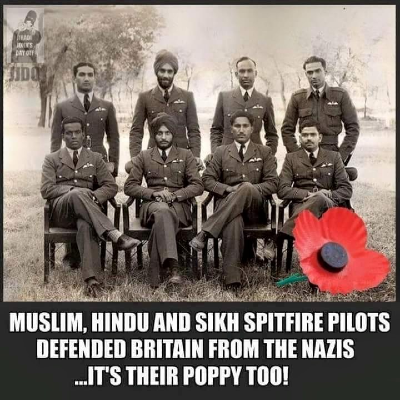

The human cost of the world wars was staggering, uniting people of every background against fascism. In the Second World War alone, tens of millions died worldwide, including over 450,000 from Britain. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records around 1.7 million men and women of the Commonwealth who lost their lives across both wars, with huge sacrifices from India, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Victory over fascism was not won by one race or nation, but by a vast coalition of ethnicities, religions and peoples determined to defeat an ideology built on division and hate.

What did Hitler and Mussolini believe?

The European axis powers, consisting of the German Nazi Party and The National Fascist Party in Italy, were ruled by two Fascist dictators, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. What makes them 'fascists' can be outlined in 3 main characteristics:

- 1) Authoritarianism- Fascist regimes concentrate power in the hands of a leader and a one-party state, dismantling checks and balances, silencing dissent, controlling the press and using state institutions to intimidate or eliminate opponents. In practice this meant legal and extra-legal repression of political rivals, censorship and the creation of a single political culture in which political pluralism was erased. For example, due to the burning of the Reichstag in 1933, Hitler used this as an excuse to blame his Communist opposition, and execute the Enabling Act to centralise power to himself.

- 2) Ultranationalism- Fascism pushes a violent, exclusionary patriotism that transforms loyalty to nation into a doctrine of racial or cultural purity. The Nazis’ “Blut und Boden” (“blood and soil”) rhetoric tied ethnic “blood” to territorial belonging and treated outsiders as contaminants to be expelled. That sentiment is the flip side of ordinary patriotism: where patriotism can mean care for one’s country, ultranationalism becomes a doctrine of exceptionalism and exclusion that justifies discrimination, dispossession and conquest.

- 3) A national rebirth- Roger Griffin’s work on fascism highlights that the “fascist minimum” is understood as applying this ultranationalist view as a vision for the future, through palingenesis (reproducing mythic national ancestors’ characteristics). Mussolini placed more emphasis on this, whereas the Nazi’s honed in on the idea of a hierarchy of race more.

A Reflection of the UK's Current Political Scene

The connection to today is not abstract. In September’s “Unite the Kingdom” rally organised by Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (Tommy Robinson) thousands gathered in London in what many outlets described as one of the biggest far-right events in recent memory; speakers at the event included known anti-Muslim and far-right figures who used explicitly exclusionary, Islamophobic language and urged policies and rhetoric that treat an entire religion as a political problem. Reporting of the event recorded calls from some speakers that Islam should be “got rid of” or treated as incompatible with Europe. The crowd was large (estimates ranged from around 110,000 to 150,000), and the scale and tenor of the rhetoric produced wide alarm among civil-society groups and commentators.

That similarity in rhetoric isn’t accidental. Nazi propaganda dehumanised Jews with metaphors of disease and parasitism. Joseph Goebbels and other propagandists repeatedly described Jews as “parasites” and “vermin,” a steady drumbeat that made mass persecution imaginable; Hitler’s early writings and speeches likewise depict Jews and other minorities as existential threats to the nation. Today’s language about “invasion,” “replacement,” “parasites” or calling whole communities a threat to the nation echoes those same dehumanising moves: first dehumanise, then deny rights, then remove protections. Pointing to migrants and asylum-seekers as a collective social problem follows exactly the rhetorical path that enabled fascist violence in the past.

But nationalism need not be poisonous. The St. George's Cross does not have to be a tool, used by the Far-Right, to hide behind covert racism. National sentiment can, and did, become the basis for progressive change: after the Second World War, many who had fought fascism turned that victory into practical commitments to social solidarity and collective provision. The welfare state, council housing and the NHS being central examples of a politics that said "we will care for each other rather than scapegoat one another". That tradition of civic responsibility and social insurance is the living, anti-fascist inheritance of those who sacrificed their lives.

Richard Murphy: Nationalism can be a tool for good!

That inheritance has been under strain since the neoliberal turn of the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher’s government, driven by conviction rather than malice, believed that freeing the market would strengthen Britain. Yet the wave of privatisations, deregulation, and cuts to social housing reshaped the country’s foundations, weakening the collective safety nets that had bound communities together since 1945. For many, living standards stagnated while public services became commodities. Today, Nigel Farage and others echo that same economic vision but pair it with division: proposing to roll back universal services like the NHS while blaming "the other", such as Syrians during the 2015 Migration Crisis, Romanians during Brexit, and most minorities since for the hardship that market policies themselves created. When economic insecurity meets scapegoating, the conditions that once birthed fascism begin to reappear.

Therefore, "Lest We Forget" has never been so important...

We will remember them. But we will also remember their cause, and we will continue to make it ours time and time again. There is no permanent victory, only the responsibility to keep fighting for a society that honours sacrifice with solidarity rather than repeating the same mistakes.

Never again, as it always has, means NEVER AGAIN.